Modifications to Working Capital and CCC

Why are prepaid expenses and deferred revenue not reflected in traditional working capital and cash conversion considerations?

General

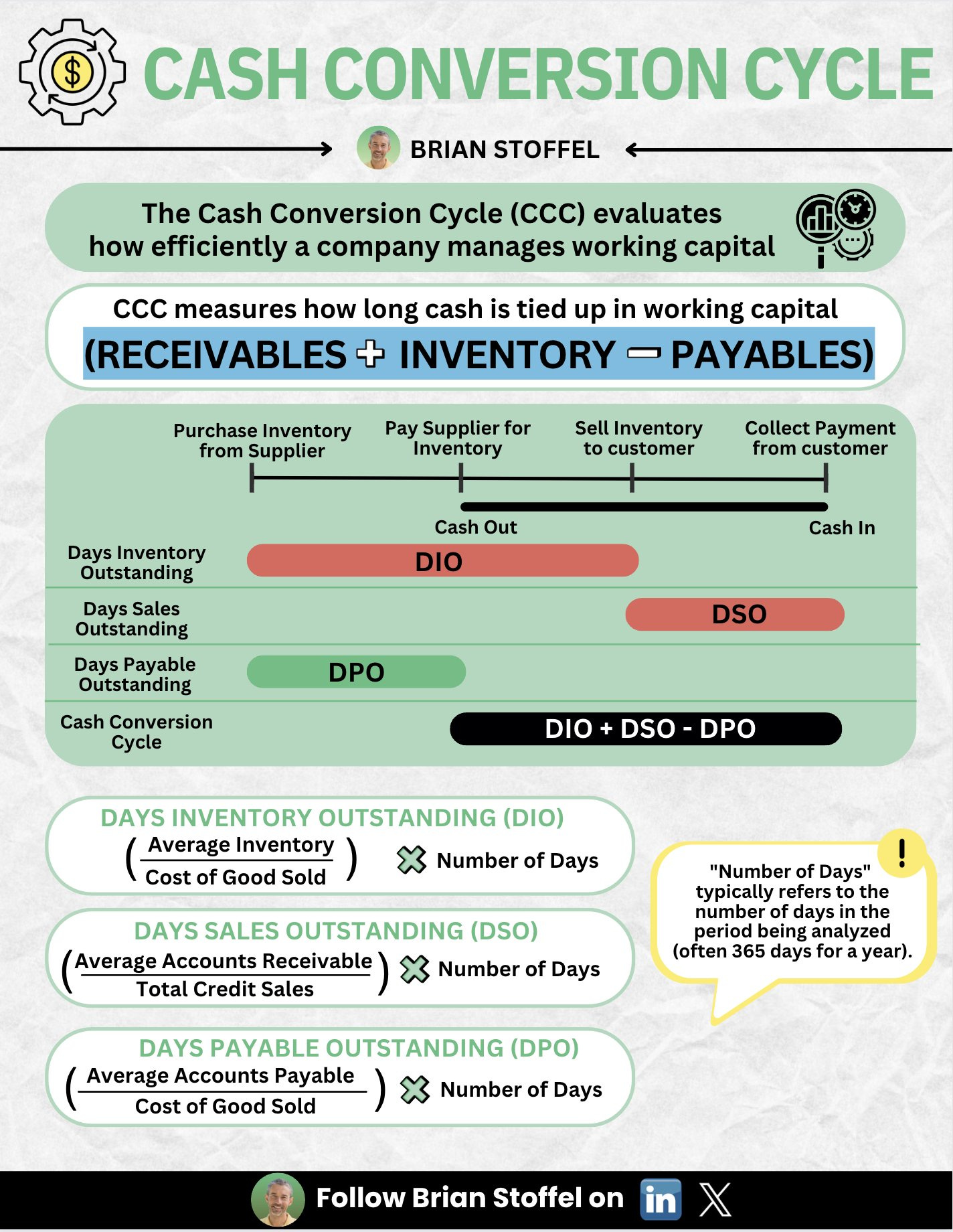

Lately, I was thinking about the traditional cash conversion cycle (CCC) and how it fails to capture float / pre-payments - partly triggered by the useful visualizations in Figures 1 and 2 below. As I argued in my earlier post, the traditional CCC calculation does not reflect upfront payments e.g. SaaS subscriptions or “Float”-style insurance capital. However, I realize now that the cash conversion calculations should prepaid reflect expenses in addition to my earlier proposal to include deferred revenue.

I borrow visualizations shared by Brian Stoffel via X to aid the discussion on traditional approaches to calculations of CCC And Working Capital (WC).

Cash Conversion Cycle And Working Capital

Looking at Figure 1, as laid out in my earlier post on CCC, cash conversion does not take into account prepaid expenses or deferred revenue. However, these are affecting the cash position of the company. If a company is in a strong bargaining position, it can demand better payment terms: it can pay suppliers later, or demand earlier payments from its customers. Consequently, the DSO bar shortens, and the DPO bar lengthens.I think the following Figure 2 on how to calculate working capital also indicates that WC calculations (bottom of the figure) fail to capture the beneficial nature of prepayments in the form of deferred revenue.

The traditional CCC neglects pre-payments e.g. for SaaS companies or insurances. However, my proposed modifications to the CCC calculation (see earlier post) also apply to traditional product-centric companies. As a company improves its negotiation position, it may demand better payment terms, e.g. earlier payment or even pre-payment from its customers, and delayed payment to its suppliers. If its negotiation position deteriorates, the opposite presents itself: suppliers ask for shorter payment terms (maybe even pre-payments), and customers may ask for delayed payment. These circumstances are captured in the Balance Sheet positions of prepaid expenses and deferred revenue. I still do not understand why the DSO, and DPO calculations, as well as WC considerations, do not take these into account even though they are clearly affecting the cash position of a business.

I think the following Figure 2 on how to calculate working capital also hints at how working capital calculations (bottom of the figure) are lacking to capture the beneficial nature of deferred revenue.

Toy Example

Let’s consider an example company after selling a product to a customer and receiving the associated payment prior to delivery. In this case, the company currently has the inventory still on the balance sheet, and has recorded the cash receipt and corresponding deferred revenue, but it is still due to pay for the inventory. It has no accounts receivable anymore. I argue that the net working capital calculation in Figure 2 understates the nature of the company’s position: assuming that the accounts payable entry cancels with the value of the inventory (and cash cancels deferred revenue). The working capital would be zero.

COGS = X

Inventory = X

Accounts Payable = X

Prepaid Expenses = 0

Deferred Revenue = Y

Accounts Receivable = 0

Cash = Y

However, the company already received the payment as deferred revenue. Hence, I argue it has negative working capital:

Artifical Example

Setting The Stage…

To motivate why my modifications of the DSO* and DPO* are truer to the CCC consider the following:

The company of the toy example has the same product in inventory, is still due to pay for the inventory, and still has already received an upfront payment from the customer (deferred revenue). According to the conventional calculation, net working capital is 0, as reasoned above (which I disagree with). CCC_1 will denote this segment’s CCC (taken from the above toy example).

However, the company also has introduced another line of product, for which it has to wait for customers to pay (i.e. it has accounts receivable entries), had to prepay its suppliers (prepaid expenses), and the inventory has already been shipped. As the prepaid expenses were canceled when taking in the inventory (that already has been shipped in this example), it has net working capital in the form of accounts receivable for this segment.

COGS_2 = X

Inventory_2 = 0

Accounts Payable_2 = 0

Deferred Revenue_2 = 0

Prepaid Expenses_2 = 0

Accounts Receivable_2 = Y

Cash_2 = Y

Here, I actually agree:

…To Present My Case

As this is an artificial example to stress my point of reasoning, I was assuming that the values for inventory, and the product pricing are identical between the product lines and only the payments differ. Here, the difference between my opinion and the traditional way of calculating WC becomes evident:

From my perspective the company should be in a neutral WC position: it has received prepayment for the first product, is still due to ship it to the customer, and is still due to settle its bills with the supplier. At the same time, it is still waiting on payment for the second product. As per my example assumptions the values cancel and the company is working capital neutral.

However, traditional calculations would have no WC use for the first product line, and a WC entry for the second, i.e. in aggregate the company has positive working capital in the traditional sense:

Updated And New Formulas

Inventory Days

Another insight (addressing an open point in my earlier article): I have come to the opinion that the DIO for the pure float style business should be zero (not 365). This was one of the options in my earlier article. I currently have no strong arguments other than the following intuition of mine: while e.g. a SaaS company cannot run out of inventory to sell and has invested in the intangible asset by way of R&D staff costs (hence the tendency of DIO towards 365 in my earlier article), a SaaS company would probably show very high CCC values when compared to more traditional companies that procure, produce, and sell tangible products via their inventory. I am still looking for a sound reasoning beyond my intution on that aspect, though.

Cash Conversion Cycle Formulas

Picking up on my earlier article, for a float-style company:

DSO* = Accounts Receivable / (Revenue / 365) - Deferred Revenue / (Revenue / 365)

DPO* = Accounts Payable / (COGS* / 365) - Prepaid Expenses (COGS*/365)

DIO* = 0

CCC* = DIO* + DSO* - DPO*

where COGS* = Deferred Revenue x (1 - Gross Profit Margin)

Working Capital Formulas

While reasoning above, I already sneaked in my proposed modication to the Working Capital to acount for prepaid expenses and deferred revenue.

WC* = Accounts Receivable - Deferred Revenue + Inventory - Accounts Payable + Prepaid Expenses

Conclusion

Picking up on my earlier article on the Cash Conversion Cycle, I provided additional reasoning why deferred revenue should be taken into account when analyzing a company's Cash Conversion Cycle and its Working Capital. My opinion evolved to include also prepaid expenses in these considerations. I think that deferred revenue and prepaid expenses offset accounts receivable and accounts payable, respectively, from a Working Capital and Cash Conversion perspective.

Your feedback will be appreciated.