"Float" & Invested Capital

Traditional ROIC and ROCE metrics flatter prepayment-based business models - in particular, high-margin subscription businesses like SaaS

Ay, ay, ayy, I'm on vacation

Every singe day 'cause I love my occupation

Ay, ay, ayy, I'm on vacation

Every single day, every, every single day

“Vacation”, Dirty Heads.

Introduction

Dear subscriber,

I genuinely like my occupation as investor allowing me to direct focus, energy and effort on what piques my interest. Today it is this post about a question, a theory, and a proposal of mine that developed a couple of days after writing a free quick and simplistic thesis about Greggs plc. That post essentially combines Greggs’ past reinvestment rates with its past performance in terms of “Return On Capital Employed” (ROCE). Now, a couple of days and several SaaS companies later I somehow got the inspiration for this post. It is in the spirit of my adjustments to the Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC):

Beware and enter at your own risk - I am no trained accountant, certified financial advisor, or certified investment advisor. I simply enjoy myself and try to lay out my logic and believe the traditional ROCE and ROIC metrics are not well suited for popular (microcap) business models that use upfront payments (i.e. float). I would very much welcome your feedback on this (as always).

What Is Invested Capital / Capital Employed ?

ROCE and ROIC are well-publicized capital efficiency metrics. They express how much a company earns relative to its capital.

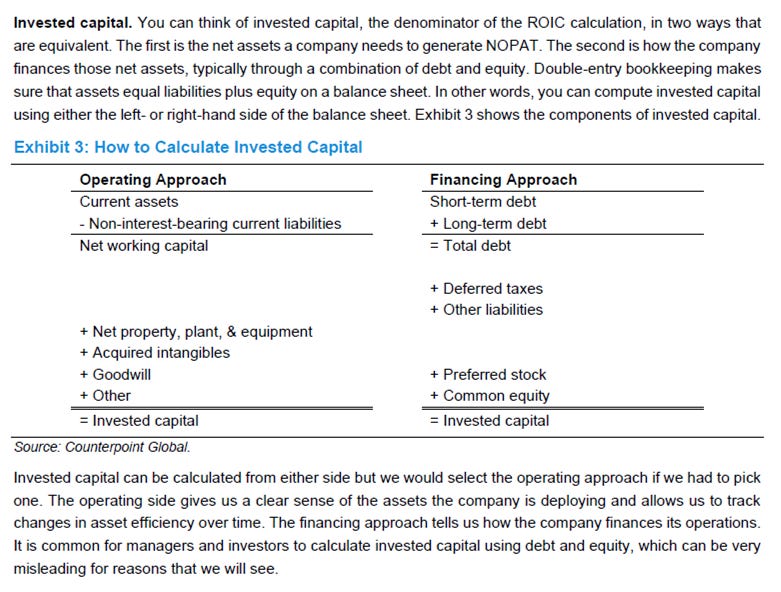

To not waste too much time writing something you probably know I used Perplexity.ai to summarize different capital efficiency metrics (the link directs you to my chat). In both metrics the term capital in the denominator can be calculated in various ways, e.g.:

Capital = Assets - Current LiabilitiesCapital = Equity + Non-current LiabilitiesCapital = Total Equity + Total Debt (including capital leases) + Non-Operating Cash

Prepayment Businesses

For this article, I focus on businesses collecting prepayments for their services (e.g. SaaS revenues, magazine subscriptions, insurance premiums) and products ahead of service or product delivery. Later, the prepayments will be recognized upon product delivery or ratably over time in the case of services. The businesses record prepayments as matching entries on the Balance Sheet that cancel each other out: a cash asset and a corresponding deferred (sometimes unearned) revenue liability. Predominantly, the deferred revenue liability is classified as current (if the prepayment is for a service to be provided over a year or less). But, it can also be a non-current liability.

Receiving prepayments for goods and services to be delivered in the future is preferable to having to lay out cash: it lowers the required working capital for the service to be provided (or product to be built or procured) - and sometimes even serves as growth capital for the business.

What Is The Problem?

Current Liabilities

While it is true in principle that until the service or product is provided to the customer the prepayment might have to be returned to the customer in full, I think that the most common case for normal business operations is that the service or product will be delivered and deferred revenues will be recognized. Hence, the liability to be expected by the business (you could say normalized liability) is only the Cost Of Goods Sold (COGS)1.

Looking at formulas 1 and 2 we see that capital excludes current liabilities - which typically carry the vast majority if not the entire amount of deferred revenues2. Thus, these formulas calculate a too-low capital intensity - the prepayment cash (or corresponding assets if the prepayment cash has already been invested) being canceled out in full by the deferred revenues. That in turn boosts the capital efficiency metrics.

Non-Current Liabilities

Probably this is less important as I understand that most prepayments are captured as current liabilities. However, the fact that in formulas 1, 2, and 3 the COGS related to non-current deferred revenue' are not reflected at all suggests that also something needs to be fixed in this regard.

How To Fix It: Adjusted ROIC/ROCE

If you agree to my line of reasoning above, the invested or employed capital should be adjusted by the expected COGS applicable to the deferred revenues. Thus I propose the following alternatives to formulas 1 - 3 (I denote the gross profit margin relevant to the deferred revenues as GPM):

Capital = Assets - Current Liabilities + GPM x (current deferred revenues) - (1-GPM) x (non-current deferred revenues)Capital = Equity + Non-current Liabilities + GPM x (current deferred revenues) - (1-GPM) x (non-current deferred revenues)Capital = Total Equity + Total Debt (including capital leases) + Non-Operating Cash + GPM x (current deferred revenues) + GPM x (non-current deferred revenues)

Note that formulas 1 and 2 have to add back the expected gross profit for the current deferred revenues and reduce the invested capital by the anticipated COGS for the non-current deferred revenues. For formula 3 it seems the COGS for the entire deferred revenue entry is missing and thus should be added back to the capital.

Does It Matter?

I believe it depends on the business:

For a 100% prepayment software business with gross profit margins approaching 100% that captures all revenue as prepayments in deferred revenues, it matters a lot as it increases the capital intensity by its entire anticipated revenue. I argue that is correct as the company would expect to convert virtually all of the received prepayment as gross profit for use in operating expenses or investments with low to no anticipated COGS.

For a more traditional business that will actually incur substantial COGS and simply collects prepayment of revenues, the impact is consequently much lower.

For companies that receive only a small portion of revenues in the form of prepayments the impact is probably negligible - but beware: I have not studied real cases to verify that claim.

Conclusion

In this post, I proposed an adjustment to the way capital is calculated for the ROIC and ROCE formulas to reflect when a company receives prepayments. Presumably, I should have discussed Michael Mauboussin’s ROIC paper also, but I believe my adjustments hold (if not, trust the paper :) ). In my opinion, the adjustments will particularly affect companies with high gross margins and significant prepayments such as SaaS companies.

Thank you for taking your time. I would very much appreciate your feedback on the proposed adjustments and the impacts they might have.

This argument is in essence also the driver behind applying the gross margin to the deferred revenue when adjusting the Cash Conversion Cycle.

About formula 3: As equity is assets minus liabilities, this formula also deducts the deferred revenues. Admittedly, the term adding back non-operating cash might rectify things, but it fails to properly account for the COGS to be expected to be incurred for the prepayments received. It would probably better to explicitly add back these as adjustments in formula 3 for clarity.